Unpacking power dynamics in Beijing

In this step we will further zoom into the power dynamics that emerged and became visible during the Beijing Conference. In addition to the strong oppositions between advocates of women’s rights and those who critique women’s rights with reference to family values, other positions and relevant critique has been voiced that tend to be overlooked when we focus only on polarization. In this article we investigate the content of the perspectives and critiques that have been voiced by actors within women’s rights and religious-political positions.

Starting with the critics of women’s sexual rights visible in the documentary, we notice their argument that western feminists and did not represent women in the Global South. Is that a relevant argument?

An article by Mary Ann Glendon, who represented the Vatican at the Beijing Conference, was published shortly after the conference in 1996 and is illustrative of this. Glendon speaks about a coalition of European Union countries that wanted the right to abortion on the agenda, while trying to remove references to the family, women’s roles as mothers, and ethics and religion from the declaration. She emphasizes the importance of acknowledging that ‘most women marry, have children, and are urgently concerned with how to mesh family life with participation in broader social and economic spheres’. Mary Ann Glendon has a point here, as this is the reality in which many women find themselves. Yet she also claims to advocate for women in the Global South, emphasizing the ‘reality of women’s lives in the global south as part of traditional families’. The fact that she herself is part of the US catholic landscape illustrates that the contestation over women’s rights in Beijing was still largely western dominated. This example illustrates the importance of considering who is making an argument, about what and whom they claim to represent.

Among the advocates of women’s rights we can observe a similar nuance. Let’s consider the reflections by Iranian women’s rights activist Mahboubeh Abbasgholizaden, who is visible in the clip you have just watched. Like Mary Glendon she offers insight into why nation state representatives from the Global South rejected the focus on sexual rights, yet for different reasons than Glendon. Her expression: ‘we say no, you colonize us by your culture and economy’ is telling for how she critiques dominant western influences, including those present in the feminist movement. Yet that does not motivate Abbasgholizaden to join the critics of women’s rights in Beijing. In fact, she tells us later in the documentary that the Beijing Conference changed her life and made her an activist in a global women’s movement to advance women’s rights that emerged after Beijing.

So while Abbasgholizaden’s critique cannot be taken as supporting the position of the Vatican, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, or the Global South governments that rejected parts of the Declaration, it is important critique that continues to be relevant until today. The critique is focused on how western actors claimed to represent women that they could not represent. Similar critique has been voiced by global south feminists. Scholar-activist Gyatri Spivak, for example, criticized Beijing for acting as a theater performance of inclusivity, while in reality the underlying inequalities between societies and the practical realities of women in various contexts across the globe were not addressed (Spivak 1996, Olcott 2013).

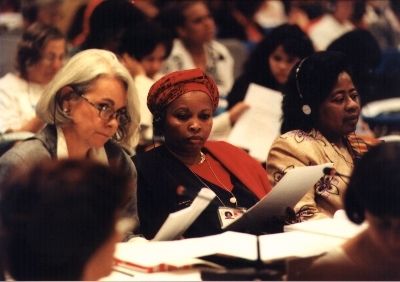

A scene at the late-night meeting of the Main Committee of the Fourth World Conference on Women held on 13 September 1995 in Beijing, China. UN/DPI Photo 131435 by M. Grant via UN Photo.

A scene at the late-night meeting of the Main Committee of the Fourth World Conference on Women held on 13 September 1995 in Beijing, China. UN/DPI Photo 131435 by M. Grant via UN Photo.

So what do we notice when we unpack the broader power dynamics in Beijing? We see various contestations emerging within the conference that point to different ‘grand schemes’ that play a role. One is religion, yet only through Europe- and US-based conservative Christians that started operating in politics and nation states with a majority Muslim population. Another is European feminism, which is (as we will explain in later steps in the course) largely secular and tends to understand religion as a threat to women. And another, underlying both, is the dominance of western power and politics visible in both religious and feminist voices. As we can see in the documentary this had implications for how the Beijing Declaration of Action was brought home to different countries across the globe. In Kenya, for example the idea quickly spread that this declaration would be used by women to overpower men. When Brenda Bartelink interviewed local religious leaders in Nairobi in 2014, this idea was still persistent and hence gender equality was still seen as a threat to the family and to Christian norms. However, at that point other initiatives had been taken to engage Kenyan religious leaders in conversations about improving the wellbeing of women with reference to both Beijing and the Bible. One female and male religious leader had volunteered to share this message in other churches and religious groups. This illustrates the importance of ensuring that women’s rights and gender equality are owned by local groups and communities, and women in particular (Bartelink and Wilson, 2020).

A scene at the late-night meeting of the Main Committee of the Fourth World Conference on Women held on 13 September 1995 in Beijing, China. UN/DPI Photo 131312 by M. Grant via UN Photo.

A scene at the late-night meeting of the Main Committee of the Fourth World Conference on Women held on 13 September 1995 in Beijing, China. UN/DPI Photo 131312 by M. Grant via UN Photo.

References

- Gayatri Chakravotry Spivak.“Commentary: “Woman” as Theatre” In Radical Philosophy 75, 1996.

- Olcott, Jocelyn. 2013. A Happier Marriage? Feminist History Takes the Transnational Turn. In P.S. Nadell & K. Haulman (eds), Making Women’s Histories: Beyond National Perspectives. New York: New York University Press.

- Brenda Bartelink and Erin Wilson. “The spiritual is political: Reflecting on gender, religion and secularism in international development” In International Development and Local Faith Actors, Edited by Kraft, K. and Wilkinson, O. London: Routledge, 2020.

Share this

Religion and Sexual Wellbeing: Pleasure, Piety, and Reproductive Rights

Religion and Sexual Wellbeing: Pleasure, Piety, and Reproductive Rights

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free